In a nondescript laboratory nestled within one of the world’s leading nuclear research facilities, scientists are perfecting an unexpected marriage of art and atomic energy. The subject of their work? Radioactive waste, transformed into stunning glass canvases that shimmer with an eerie luminescence. This is not alchemy, but a cutting-edge solution to one of humanity’s most persistent environmental dilemmas—how to safely contain nuclear byproducts for millennia. The resulting glass-waste matrices, though born from necessity, possess an unsettling beauty that challenges our perceptions of danger and decay.

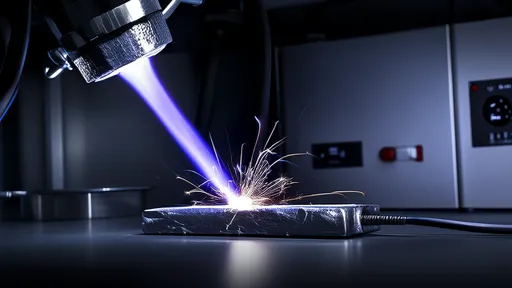

The process, known as vitrification, involves encasing high-level radioactive waste in molten glass at temperatures exceeding 1,000°C. As the mixture cools, it solidifies into a durable, chemically stable form that locks radioactive isotopes within its atomic structure. What emerges are glossy black or amber-colored blocks—some translucent, others opaque—that resemble obsidian or antique stained glass. These glass monoliths, destined for deep geological repositories, will outlast pyramids and skyscrapers by orders of magnitude. Yet in their polished surfaces, one can discern swirling patterns reminiscent of abstract expressionist paintings, a serendipitous artistry born from molecular chaos.

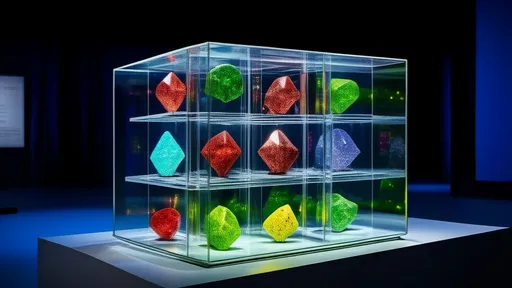

Curators at the Museum of Anthropocene Relics have begun collecting cross-sections of these waste-glass specimens, displaying them alongside interpretive materials about their 24,000-year half-lives. The exhibits provoke uncomfortable questions: Can something so hazardous also be aesthetically compelling? Does rendering toxicity beautiful make it more acceptable? Critics argue this approach risks trivializing nuclear dangers, while proponents see it as a powerful communication tool—a way to make imperceptible radiation visceral to the public. The glass’s visual appeal becomes a paradox, simultaneously attracting viewers while repelling them with its lethal payload.

Beneath the aesthetic debate lies remarkable materials science. The glass matrices must withstand earthquakes, groundwater corrosion, and gamma radiation bombardment without fracturing. Researchers have experimented with adding rare earth elements to create vibrant blues and greens in test batches—colors that serve no practical purpose but reveal how artistic impulses persist even in containment technology. Some formulations accidentally produced iridescent effects akin to medieval cathedral glass, prompting physicists to joke about designing a nuclear chapel for the far future.

As climate change forces reevaluation of nuclear power’s role, these glass-encased relics may multiply. Their existence forces a cultural reckoning: How will civilizations 300 generations hence interpret these glittering, deadly time capsules? Perhaps as warnings, or perhaps—disturbingly—as invitations to decode their latent energy. The vitrified waste’s beauty becomes its own kind of containment strategy, using fascination as an additional barrier against careless handling. In this light, aesthetics transforms from mere accident to essential safeguard—a reminder that solving humanity’s greatest challenges may require appealing not just to reason, but to our innate attraction to the sublime.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025