In the remote Arctic archipelago of Svalbard, a concrete wedge juts defiantly from a frozen mountainside – its prismatic facade reflecting the midnight sun in fractured rainbows. This is the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, humanity's ultimate botanical backup drive where over a million seed samples sleep in minus-18°C stillness. But what appears as a sci-fi freezer for doomsday crops reveals itself upon closer inspection as something far stranger: a living sculpture of genetic potential, a biological time capsule where evolution's blueprints are preserved in suspended animation.

The vault's architecture tells its own story – its entrance portal thrusts upward like a sprouting seedling, while interior corridors plunge downward into permafrost like roots seeking nourishment. This is no mere warehouse. Norwegian artist Dyveke Sanne embedded prismatic steel panels in the concrete to create ethereal light effects, ensuring the structure serves as both utilitarian storage and monumental land art. "We're not just archiving seeds," explains vault coordinator Åsmund Asdal, "we're sculpting the raw material of civilization's next chapter."

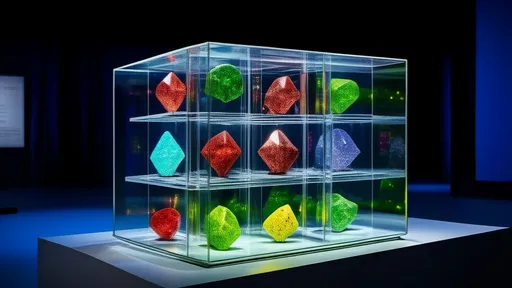

Deep within the vault's chambers, each aluminum seed packet becomes a miniature Louvre for genetic masterpieces. The 1500+ global genebanks contributing samples don't simply dump seeds into boxes; they curate evolutionary artistry. Some packets contain drought-resistant sorghum whose genomes remember the Sahel's harshest famines. Others safeguard ancient Peruvian potatoes that weathered El Niño events before the Spanish conquest. When researchers from the International Rice Research Institute deposited seeds of a submergence-tolerant "scuba rice" variety, they included handwritten notes about the Cambodian farmers who cultivated its ancestors during monsoon floods.

The vault's very existence sparks philosophical quandaries about humanity's relationship with nature. Are we playing Noah building an ark for the Anthropocene, or have we become genetic sculptors remolding evolution's clay? Crop scientist Dr. Cary Fowler, who conceived the vault, describes it as "a library where every book is a recipe for rebuilding ecosystems." During Syria's civil war, researchers retrieved duplicate seeds of drought-resistant crops originally stored there by Aleppo's genebank – marking the vault's first loan and proving its value as a living repository rather than a museum exhibit.

Climate change has transformed the vault's surroundings into a surreal diorama of planetary transition. Permafrost that was meant to provide natural refrigeration now requires artificial cooling as Arctic temperatures soar. The entrance tunnel, designed to stay dry through snowfall, confronted unexpected glacial meltwater in 2017 that turned into an ice sculpture at -3°C. These paradoxes highlight the vault's dual nature: both a fortress against ecological collapse and a mirror reflecting our disrupted climate systems.

Indigenous communities have contributed unexpected dimensions to this genetic monument. The Cherokee Nation became the first U.S. tribe to deposit seeds, including their sacred "Trail of Tears" corn carried during forced relocations. Sámi herders from Arctic Scandinavia provided cloudberry varieties that track centuries of seasonal shifts in their migratory patterns. "These seeds aren't just DNA," emphasizes Tero Mustonen from the Snowchange Cooperative, "they're living memories of how cultures adapt to Earth's changes."

The vault's contents are constantly evolving in unexpected ways. After Norwegian brewers deposited ancient barley strains, geneticists discovered dormant enzymes that could revolutionize beer production. Mexican wild corn varieties, stored as climate insurance, revealed disease-resistant traits that may save commercial crops from emerging pathogens. This dynamic interplay between preservation and discovery positions the vault less as a static archive and more as an active laboratory where evolution's greatest hits get remixed for future challenges.

As the Anthropocene accelerates, the seed vault's symbolism grows more complex. Its very existence acknowledges ecological fragility while demonstrating human ingenuity. The concrete exterior weathers polar storms as reliably as the seeds inside will weather global crises. Perhaps this explains why the structure has become an unlikely pilgrimage site – where climate activists hold vigils, artists create installations, and philosophers ponder whether we're preserving nature or preserving ourselves. In this frozen gallery at the world's edge, each seed packet hangs like a brushstroke in a still-growing portrait of resilience.

New deposits continue expanding the vault's living collection. Brazilian scientists recently added Amazonian fruit trees with medicinal properties unknown to Western science. Ethiopian researchers contributed teff grains containing drought adaptations from the Horn of Africa's deepest droughts. With each addition, the vault becomes more than a backup drive – it evolves into a three-dimensional atlas of human-nature coevolution, where every seed tells a story of survival, and every variety represents a different path through the Anthropocene.

The ultimate test of this genetic sculpture garden may come sooner than expected. As crop diseases spread faster in warming climates and extreme weather decimates harvests, agronomists increasingly tap the vault's reserves. What began as an apocalyptic insurance policy has become an active toolkit for climate adaptation. The seeds frozen here aren't just relics of agriculture's past – they're prototypes for food systems we haven't yet imagined, waiting patiently in their aluminum frames like embryos of future landscapes.

Standing before the vault's glowing entrance as the Arctic wind howls, one senses the profound contradiction this place embodies. It's simultaneously a monument to human foresight and a memorial for ecological losses not yet suffered. The seeds inside represent both endings and beginnings – the extinction of certain growth patterns and the birth of others. In this concrete embrace of genetic potential, perhaps we find the ultimate artistic medium: life itself, paused mid-stride, awaiting its next evolutionary act.

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025

By /Jul 31, 2025